A Comment on the Fight against Corruption and Indian Democracy

byThe author is a Professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi. His views are his own.

An anti-corruption movement in India, run by a set of elites primarily from Delhi, has put poor Anna Hazare out in front and called itself a national movement. Their key demand is an anti-corruption citizen ombudsman bill, the Jan Lokpal Bill (JLPB), which would create an independent body investigating corruption cases, completing the investigation, and holding a trial within a specific time frame.

Is the Jan Lokpal Bill (JLPB) the path toward a corruption-free India? Presumably, if the answer were a straight forward “yes,” we would probably have had a JLPB by now. The founding fathers of this nation have gifted us a Constitution which laid the foundation for a vibrant democracy, a secular republic, and a federal structure. This strong foundation has not only kept this country together despite its adversities, but it has also been able to accommodate the needs and aspirations of people of diverse cultures, ethos, and religion with a fair degree of success. If the JLPB or a law of such nature were so important, certainly our founding fathers would not have deprived us of that perceived magic wand to keep India corruption-free. In the existing system itself there are sufficient institutional safeguards against corruption. Unfortunately, corruption continues to grow despite these safeguards. Public anger against corruption is justified, but Anna’s methods are not.

If Anna and his team believe in India and its constitutional democracy, instead of fueling mobocracy in the name of democratic rights, they should start discussing a JLPB with the government and then depose before the Parliamentary Standing Committee if they have any further issues after that. They should respect the institutions and elected government, instead of taking the whole country hostage. Indulging in lawlessness to bring in a law is the ultimate irony of this movement. Things have gone to such an extent that Anna seems to have given orders to his followers to go and protest in front of the MP’s and MLA’s residences to push for his version of the JLPB. One fails also to understand: why is the government in such circumstances a mute spectator? One can only hope that this does not turn violent.

If we look at it dispassionately, corruption is not an Indian phenomenon alone. Corruption exists in every society; only the degree and nature differ. Instead of defaming India, it is important to understand (1) if the Indian system is relatively more corrupt than many others, (2) what breeds and perpetuates that corruption, and (3) whether the JLPB can be the solution.

If corruption is defined as the misuse of public office for private gains, is it due to an absence of a JLPB? The answer is a big “no.” There are multiple reasons for corruption and the likely primary factors are illiteracy, poverty, lack of awareness about one’s own rights, excessive government control in many sectors, and administrative inefficiency and complicated acts and rules that leave too much discretion in the hands of public servants. If corruption needs to be eliminated from the system, we need to tackle all of these simultaneously, which is a much more complex task than enacting JLPB.

An overarching JLPB won’t help. In fact, it could make matters worse. The solution probably lies in making clearly defined acts and rules, thus removing discretionary power from the hands of public servants, and also making heavy investments in the social sector for human development and awareness. Above all, we need unambiguous, implementable rules to tackle corruption.

Targeting politicians won’t help. Politicians are very much a part of the same society. It is difficult to imagine that bureaucrats and politicians are the only corrupt lot in our society. If India is more corrupt than many other nations, we all have played our own role to make it so and we need to correct that before holding candle light processions in support of Anna in Delhi streets. How excessive government control in various sectors of the economy encouraged corruption is a well-known story, and, if we look at the telecom sector, what happened with decontrol is also well known.

Is the intensity of corruption the same across India? The 2005 “Indian Corruption Study,” by Transparency International (TI) and the Centre for Media Studies (CMS), is the largest corruption survey, with 14,405 respondents, spread over 151 cities, and 306 rural areas within 20 Indian states. The study revealed that there have been substantial variations in levels of corruption across Indian states. The survey focused on corruption in the public sector. More specifically, it captured the level of “petty corruption” encountered in securing 11 different public services: the income tax bureaucracy, municipal services, the judiciary, the Rural Financial Institution (RFI), Land Administration, police, public schools, water suppliers, electricity suppliers, government hospitals, and ration cards. According to this survey, Kerala is the least corrupt state and Bihar is the most corrupt, with an index value of corruption at 2.4 and 6.95 respectively. What explains this variation within the same institutional structure—have Anna and his team considered this?

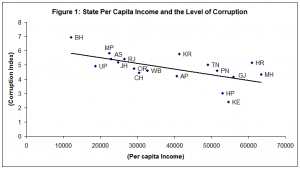

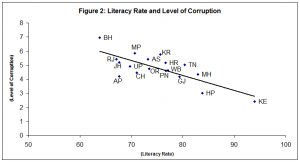

If we plot this corruption index against per capita state income and literacy we do see a negative relationship between the two (See Figure 1 & 2). In other words, with higher levels of income and education, corruption does come down.

Using this data, a paper by Nicholas Charron of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden (The Correlates of Corruption in India: Analysis and Evidence from the States) proved through a robust econometric estimate that corruption in India is negatively related to development and decentralization. Sadly, after almost 20 years of the 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments, we hardly have any effective decentralization, except in a few states, and the development disparities across states continue to increase.

So what is the solution? The solution lies in empowerment of people through massive public investment in basic health, primary education, and infrastructure to ensure equitable development to unleash the growth potential and economic opportunities for those who are still excluded from and get exploited by the system. With our without JLPB, empowerment of people would bring down corruption substantially. After all, Anna’s team is comprised of a set of intellectually-enlightened elites who have previously worked at high levels in the Indian bureaucracy, and some of them continue to be part of the Indian judiciary. I hope they would understand these basics. If they don’t, then I would only thank god that they are no longer a part of the Indian governing structure influencing and executing public policy.

Email: pinaki@nipfp.org.in