Austerity and Growth: Missing the Point

byThe pseudo-debate about whether Keynesians and other fellow travellers ought to be embarrassed when governments that engage in fiscal austerity nevertheless experience positive economic growth rates has become a distraction.

For countries like the US and the UK, it is possible under current circumstances for governments to implement budget cuts and still see their economies grow. But the truth of that statement is not fatal to the Keynesian-inspired critique of austerity policies; it is not by any means the end of the story. The more meaningful question is this: What would have to happen in these economies for significant growth to occur in the midst of budget tightening?

Finding an answer to that last question is one of the strengths of the approach to thinking about the economy pioneered by Wynne Godley, and fleshed out further in the Levy Institute’s strategic analysis series. This approach also provides a clear understanding of how deeply irresponsible it is to cut government spending under present economic conditions: because the danger, given the state of the US and UK economies, is not just that budget cuts might slow down the economy, but that they might not.

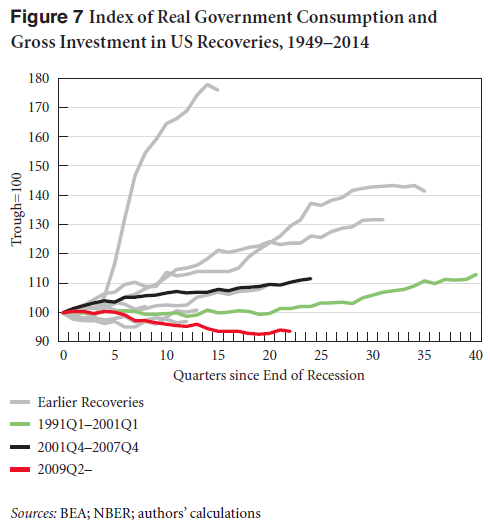

Let’s look at the United States in particular. In their just-released report, Dimitri Papadimitriou, Greg Hannsgen, Michalis Nikiforos, and Gennaro Zezza point out that, with the exception of a short cycle in the ’70s, “there has been no other recovery in the modern history of the US economy in which government spending decreased in real terms.”

The Congressional Budget Office is predicting that the budget deficit will continue to shrink over the next few years, from 2.8 percent of GDP in 2014 to 2.4 percent in 2018. At the same time, the authors note, the CBO is telling us that GDP will grow at 2.8 percent, 3 percent, 2.7 percent, and 2.1 percent in 2015, ’16, ’17, and ’18, respectively. If we assume that both of those forecasts (for the budget deficit and GDP growth) come true, what would the rest of the economy need to look like?

The United States has run current account deficits, which act as a drag on economic growth, for decades. And despite the recent increase in net exports of petroleum products, which has helped keep the US trade deficit from returning to its sky-high precrisis levels, there is little reason to think that the external deficit will substantially improve over the next few years (if anything, the authors argue, it is likely to get worse. There’s more on recent developments in the foreign sector beginning on p. 6 of the report).

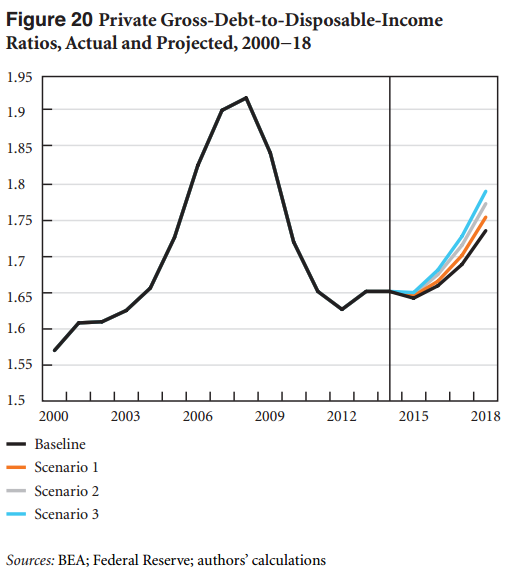

That being the case, GDP growth rates of the sort projected by the CBO can only come to pass on the basis of a rise in private sector spending. In fact, Papadimitriou et al. show that private sector spending would have to expand so much that it would exceed private sector income for the first time since the crisis. In other words, growth would depend on rising private indebtedness.

If the dollar continues to appreciate further and the economies of US trading partners end up performing worse than the IMF expects (a very real possibility, the authors point out, given the optimism of IMF forecasts), this increase in private sector spending over income — and thus the increase in the private debt-to-income ratio — would have to be even larger. Here’s what that would look like (in the chart below, “Scenario 1” corresponds to slower growth among US trading partners [by 1 percent of GDP annually], “Scenario 2” to a 25 percent appreciation of the dollar over the next four years, and “Scenario 3” to a combination of the two):

If private spending doesn’t blow up in this way, the CBO’s optimistic growth projections won’t come about. But if growth does occur, it can only do so (given the external deficit) through a process that raises the debt-to-income ratio of the private sector. As the authors point out, this is precisely the same process that led to the Great Recession and its aftermath.

What’s worse, the state of income inequality in the United States is such that this increase in private debt will be borne disproportionately by households in the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution. Unlike the federal government, which can service its debt through mere keystrokes, US households cannot sustain rising debt ratios of the sort portrayed in the chart above (though the amount of public hand-wringing spent on the debt of the former, as compared to the latter, would suggest the opposite). As Papadimitriou et al. write:

“Increased borrowing of one kind or another can often be sustained for a long time … but eventually, retrenchment takes place relative to incomes. The consequences of any further retrenchment in debt-financed consumer spending would be felt throughout industries that produce for the US consumer, and again, as we noted above, the recovery in real private domestic consumption is already weak relative to any previous recovery.”

To bring this back to the tired discussions surrounding austerity policies: yes, it is possible for the United States to have both tight budgets and rising GDP over the next few years. Fiscal conservatism doesn’t make economic growth impossible in the near term — it makes it impossible to grow without increasing financial fragility. In the absence of a significant increase in net exports, keeping the government budget on its current track will lead to either stagnation or an acute crisis.

Austerians in the United States and elsewhere have been allowed to portray themselves as the champions of steely-eyed realism and prudence. In reality, unless their budget proposals come attached with some workable plan to substantially reduce trade deficits, they are courting private-debt-driven financial crises. In any meaningful sense, they are the true practitioners of fiscal irresponsibility.