Did Ms. Rousseff’s Epiphany Come Too Late?

byby Felipe Rezende

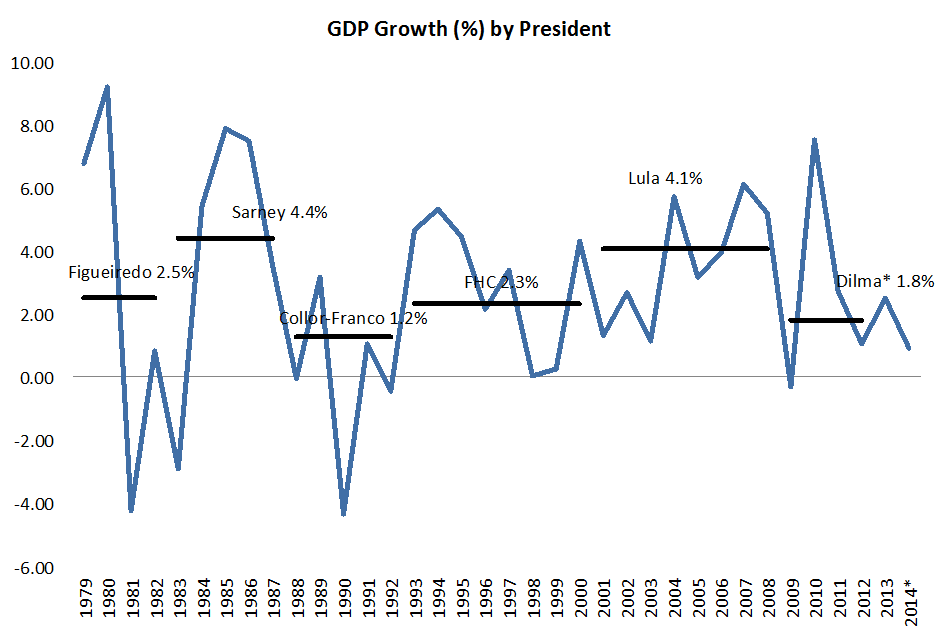

If you’ve been tracking the news on Brazil’s presidential election, you already knew that incumbent Rousseff will face Neves in a runoff election for Brazil’s presidency on October 26th. The tight election reflects the perception of a downward trend of the nation’s economic outlook augmented by news that Brazil’s economy has fallen into recession in the first and second quarters of 2014. This really isn’t looking like the election the Workers’ Party expected. Brazil’s unemployment rate has hit record lows, real incomes have increased, bank credit has roughly doubled since 2002, it has accumulated US$ 376 billion of reserves as of October 2014 and it has lifted the external constraint. The poverty rate and income inequality have sharply declined due to government policy and social inclusion programs, it has lifted 36 million out of extreme poverty since 2002. Moreover, the resilience and stability of Brazil’s economic and financial systems have received attention as they navigated relatively smoothly through the 2007-2008 global financial crisis. Brazil’s response to the largest failure of capitalism since the Great Depression included a series of measures to boost domestic demand.

So, what happened? The reason is fairly obvious, in the aftermath of the global financial meltdown, policy makers misdiagnosed the magnitude of the crisis, the changing circumstances because of it, and ended up withdrawing stimulus policies too early. The premature withdrawal of stimulus measures opened up space for critics, such as the main centre-right opposition party, to blame Ms. Rousseff’s administration as being excessively interventionist leading the Brazilian economy to perform poorly during the past four years. It fueled Mr. Neves’s campaign to convince anti-Rousseff voters he can get Brazil’s economy back on track.

Five years after the crisis where do we stand?

The Brazilian economy in the New Millennium experienced extremely favorable external conditions such as increasing global demand for emerging market exports and rising financial flows to emerging markets (Kregel 2009). Some critics of the Brazilian government argue that the positive economic performance during the past decade was solely due to external tailwinds fueled by the boom in commodity prices, buoyant external demand, and massive foreign flows into Brazil’s economy. This group tends to overlook domestic policies designed to foster private demand. Brazilian economic policymakers, by contrast, proudly point to government policies designed to boost growth.

To be sure, the positive economic performance was driven by both domestic and external factors. Under the Lula administration, the Brazilian economy grew generating jobs, raising real incomes (minimum wage increases, income transfer programs), reducing poverty and income inequality. It also boosted consumption through domestic credit expansion. During the past decade banks (public and private) have roughly doubled their lending as a share of GDP increasing consumer loans — in particular payroll deductible and auto loans — mortgage loans, and business loans. Moreover, following the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, public investment increased (PAC I and II, long term investment funding via BNDES, housing financing (My House, My Life) to meet Brazil’s investment needs and to act as a countercyclical tool to offset the decline in private demand. Even though the administration moved in the right direction in an attempt to shift its development strategy to domestic demand-led growth, it committed a strategic error by intervening in the economy with government initiatives that were too small to generate improvements in the nation’s economic outlook, partly due to its belief that it lacked the financial resources to foster the domestic demand. Though the global financial crisis made once again evident that markets are not efficient or stable and that government intervention is necessary to dampen market instability, the current administration has faced fierce attacks all the way from anti-Workers’ Party groups and the right-wing media pointing out that the current crisis is a failure of government due to its actions and interventions, not free markets. With the stimulus perceived as a failure, opponents of it argue that state intervention is the problem, fueling the opposition presidential candidate campaign. Against this background Mr. Neves has emerged as the market favorite, who is embracing the return of pro-market policies and fiscal austerity implemented in the 1990s and early 2000s, that failed to deliver growth and development. Mr. Neves has announced that if he wins the election, then Arminio Fraga, former managing director of Soros Fund Management and founder of the investment company Gavea Investmentos, will become his minister of finance.

The impacts on the Brazilian economy of a new global structure

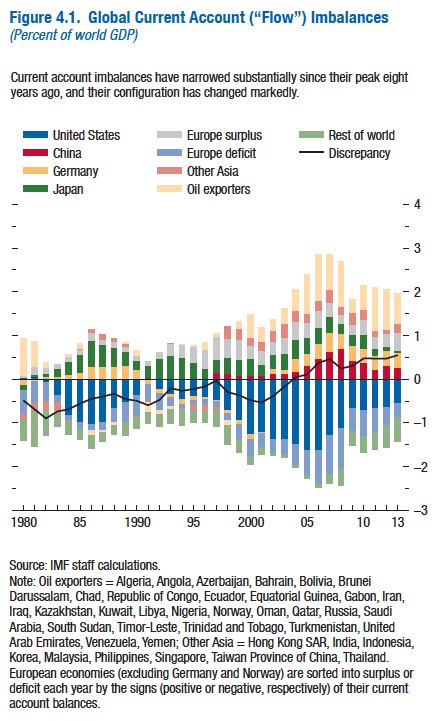

The conditions that prevailed prior to the 2007-2008 GFC, which benefited developing economies, were characterized as a bubble and the positive conditions[1] experienced by developing economies are unlikely to return.

Kregel (2009) characterized

the evolution of developing countries in the New Millennium as a “bubble”, for if the US economy was experiencing a financial bubble the counterpart of that bubble was the extremely beneficial conditions in developing countries and in particular in Latin American emerging markets…we cannot foresee a return to the extremely positive conditions experience by developing countries in the recent past.

virtually all of the positive performance that led to achieving the Brazilian dream of meeting the target of the BRICs appear to be linked to a financial model and financial flows that is not likely to be reestablished. The degree of leverage that had become normal in developed country financial institutions will not return, the leverage generated by financial derivatives will now be couched in much stronger margin requirements. This will not only mean lower asset prices but lower global demand for emerging market exports and thus reduced financial flows to emerging markets including the BRICs…there is general similarity across all BRIC economies for they all depend on expanding demand through increasing global trade and global imbalance financed by global financial flows. (Kregel 2009:353)

This view is also present in a report released by UNCTAD

Prior to the Great Recession, exports from developing and transition economies grew rapidly owing to buoyant consumer demand in the developed countries, mainly the United States. This seemed to justify the adoption of an export-oriented growth model. But the expansion of the world economy, though favourable for many developing countries, was built on unsustainable global demand and financing patterns. Thus, reverting to pre-crisis growth strategies cannot be an option. Rather, in order to adjust to what now appears to be a structural shift in the world economy, many developing and transition economies are obliged to review their development strategies that have been overly dependent on exports for growth. (UNCTAD, Trade and Development Report, 2013, p.1-2)

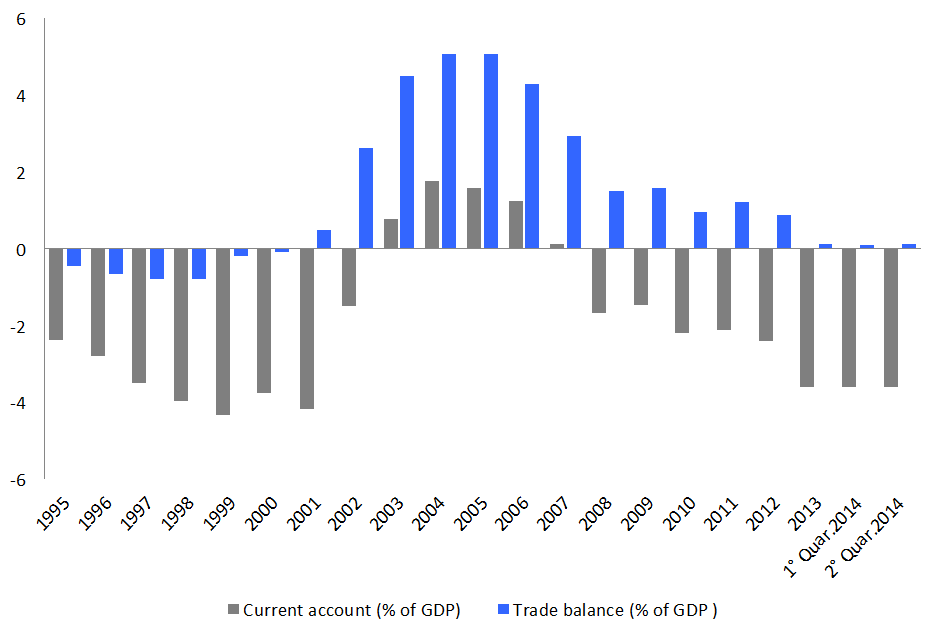

The bubble period has shown a remarkable turnabout of the current account balance, from a deficit to a surplus position.

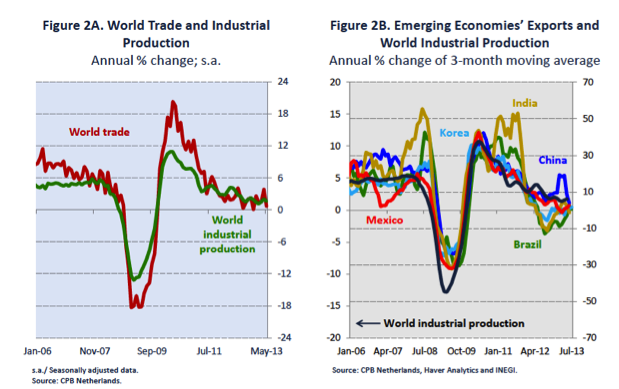

The consequences of the crisis were clear. Global financial markets and US households started deleveraging thus producing a new global structure impacting global trade, industrial production, and finance.

Source: Agustín Carstens, Governor, Banco de México , August 23, 2013. The Economic Policy Symposium on “Global Dimensions of Unconventional Monetary Policy.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming

Following the Great Recession, the combination of substantial US private sector deleveraging and shrinking the US current account deficit led to a sharp decline in the demand for emerging market exports due to structural changes in international markets. An export led growth strategy requires at least one nation to run current account deficits. Given the absence of robust external demand and the conditions that prevailed before the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, it becomes important to shift Brazil’s development strategy towards the domestic market to fill the spending gap.

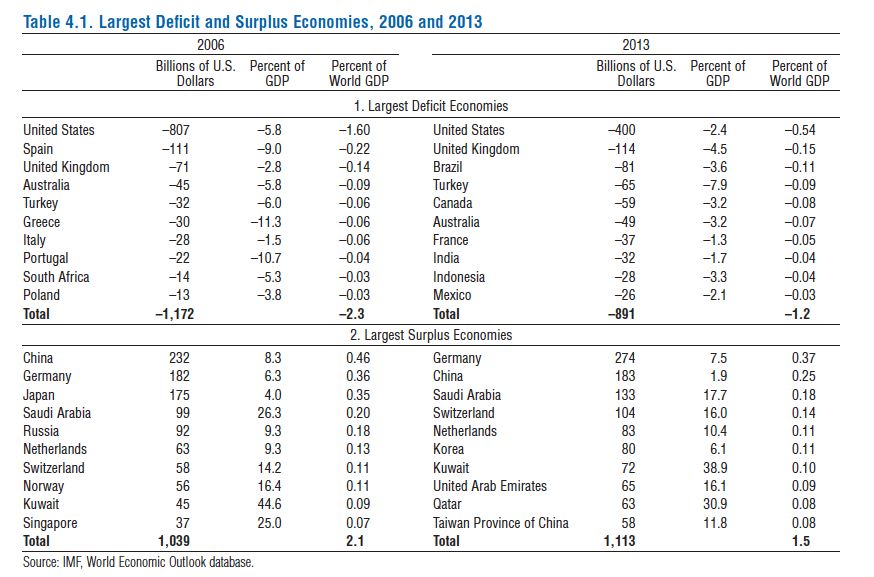

The impacts of the crisis in Brazil, in particular, were substantial. It moved from a current account surplus equal to 1.25 percent of GDP in 2006 to a deficit equal to 3.6 percent of GDP in 2013 being third-largest deficit economy (after the US and UK) in the world according to a recent IMF report.

To sum up, key policy makers failed to see the obvious. US demand, financed by the deregulated US financial system and shadow banking institutions, made trade the engine of global growth and the rest of the world responded by adopting policies of export-led growth. The exceptionally positive performance of the Brazilian economy during the New Millennium characterized by high growth rates, external surplus balance, rising foreign direct investment flows, rising employment levels, and improving debt burdens of the public sector were the counterpart of deregulated developed country financial systems, which drove asset prices up such as commodity prices improving developing country terms of trade, allowed rising private sector debt thus supporting the demand for imported goods, and generated a positive carry trade resulting in short term capital flows to emerging markets (Kregel 2009, p. 5).

Sectoral financial balances in the Brazilian economy: the basic macroeconomic accounting identity

Following account identities and stock-flow consistency, we find that the surplus of the non-government sector equals the deficit of the government sector. It follows that if the non-government sector desires to run surpluses, the government sector must run a budget deficit. Simple. Moreover, government deficit spending adds to the non-government sector’s net financial assets, where nongovernment financial balance equals the domestic private sector financial balance plus the balance of the rest of the world. The three-sector balance accounting identity shows the interaction between the government sector, the domestic private sector — households and firms — and the foreign sector.[2] In the aggregate, if one sector runs a surplus at least one sector must run a deficit. When the government sector deficit spends it creates private sector surplus, all else equal. On the other hand, government surplus destroys nongovernment sector’s net nominal wealth. In order for the private sector to continually run surpluses, then either the government or the foreign sector must run a deficit, that is from the identity Private Sector Surplus = Public Sector Deficit + Current Account Surplus.

Domestic Sector Balance = Government Sector Balance + External Sector Balance

or

DSB = GSB + ESB

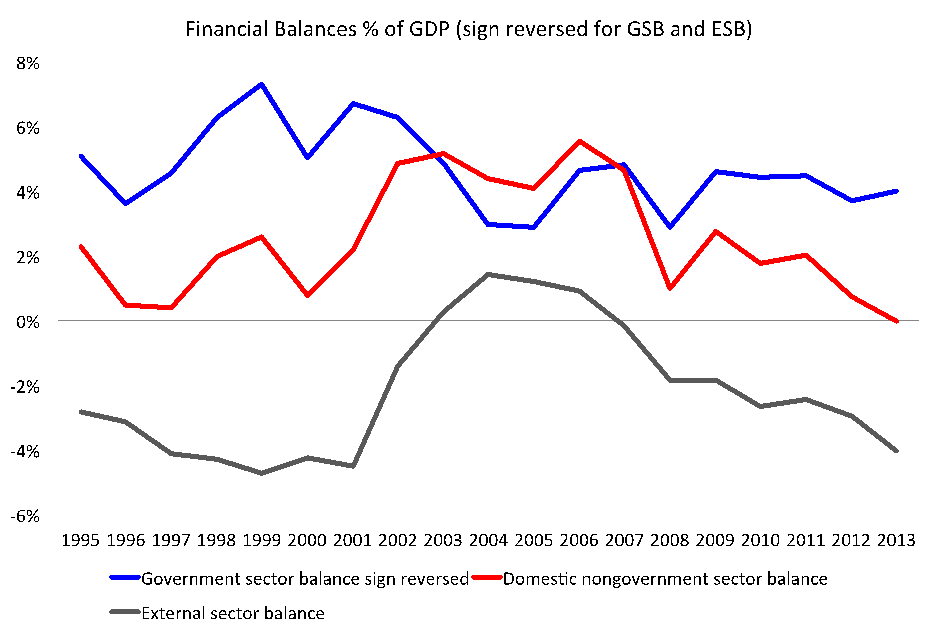

The surplus of one sector must be mirrored by another sector running a deficit. The sectoral financial balances identity is also useful to distinguish between currency issuer (the federal government) and currency users (that is, the nongovernment sector which is comprised of the domestic private sector and the external sector). If the government sector runs a deficit then the nongovernment sector accumulates net savings. To illustrate this point, we can use the financial balances equation applied to the Brazilian economy. Remember that the sum of all balances, that is the private sector, the government sector, and the foreign sector must equal to zero. The following chart shows the sectoral financial balances for Brazil’s economy.

Source: IBGE and CEMEC

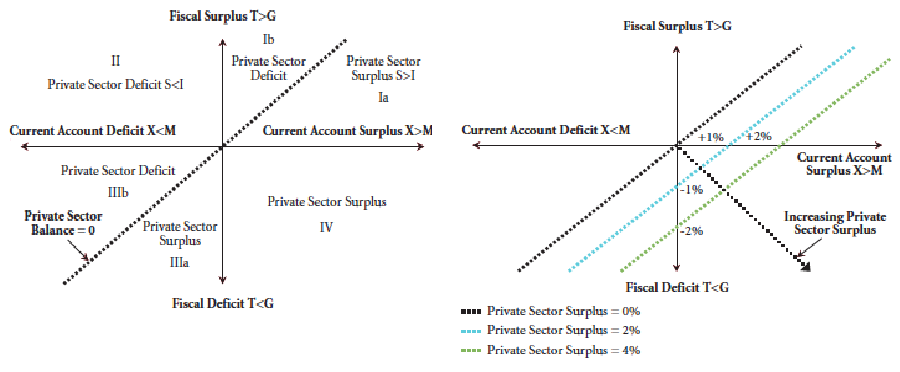

We can distinguish the beginning of the new millennium for Brazil’s economy between two periods: one characterized by the U.S. financial bubble that contributed to the creation of current account surpluses in emerging economies until the onset of the GFC and the other initiated in 2007 when Brazil posted a persistent current account deficit. During the bubble phase, the domestic private sector ran an average surplus balance equal to 4.8% of GDP from 2002 to 2007 as a result of the combination of current account surpluses (average 0.4% of GDP) and government fiscal deficits (average 4.4% of GDP). It allowed the net acquisition of financial assets by the domestic private sector to exceed the net issuance of liabilities, which translated into rising net financial wealth in the private sector. However, during the second phase, from 2008 to 2013, the domestic private sector ran an average financial balance equal to 1.4% of GDP, the external sector an average deficit equal to 2.6% of GDP, and the government sector posted an average deficit equal to 4% of GDP. We can portray those two periods using the financial balance map suggested by Robert Parenteau to simulate the impacts of changes in the government and external balance on the domestic private sector.

Source: Kregel 2011, p.6

During the bubble phase, the Brazilian economy experienced current account surpluses and the government sector ran a deficit. Thus, the domestic private sector balance was in a surplus position. This situation is depicted in quadrant IV in the figure above. However, after the global financial crisis there was a sharp reversal of the current account balance into a deficit. On the figure above, we are now on Quadrant III. Given the persistent and deterioration of current account deficits to 4% of GDP in 2014 from 0.1% in 2007 and the rigidity of the fiscal balance, the private sector is running a deficit. The net issuance of liabilities exceeds the acquisition of financial assets by the domestic private sector, the private sector shows dissaving. This is an unstable financial profile and is a significant source of financial fragility in the private sector. As the now famous economist Hyman Minsky reminded us, the growth of private sector indebtedness in excess of income leads to increasing fragility and lower margins of safety. If the private sector attempts to net save 4-5% of the GDP (the 2002-2007 average) to deleverage their balance sheets, it would require bigger fiscal deficits in order to allow them to net save and to contain deflationary forces in the presence of current account deficits. The major reverse in the private sector behavior limits the impacts of the Big Government and the Big Bank dragging employment and output.

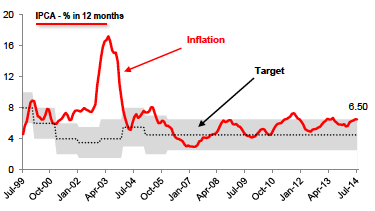

Brazil is already dealing with the consequences of an external surplus reversal. Domestic demand and activity show signs of weakness including declines in industrial production, capacity utilisation, and net job creation has slowed significantly. The Brazilian central bank has initiated a series of rate hikes in an attempt to bring inflation to its target.

Source: IBGE

Five years have passed since the federal government adopted stimulus measures to save jobs and constrain a shortfall in overall spending. The combination of tax cuts and increases in government expenditures provided a temporary boost. Even though there were positive short-run and long run effects from the federal government stimulus, it was too short-lived to accommodate changes in the new global structure and the decline in domestic demand after the 2007-2008 GFC. The delay to make the transition to domestic demand-led policies led to Brazil’s lackluster growth. With government initiatives perceived as a failure, the debate shifted to obsessive concern over budget deficits fueling opponents call for fiscal austerity. So why does conservatives believe the Dilma administration was a failure? Because the Brazilian economy continued to perform poorly suffering the impacts of the new global structure and government stimulus that are too small to spur growth. With Ms. Marina Silva’s endorsement of presidential candidate Aecio Neves in the October 26 runoff against Ms. Rousseff, the economic agenda favor fiscal austerity, the return of a minimal state, and failed orthodox policies. It is being driven by the false belief that budget deficits crowd out private spending, high deficits must lead to inflation, and that government cutbacks are necessary to restore business confidence. More recently Arminio Fraga, an economic adviser to presidential candidate Aecio Neves, has argued for fiscal tightening — either through raising taxes or cutting government spending.

We can simulate three scenarios for Brazil after elections: a) fiscal austerity; b) declining current account deficits; and c) rising government deficits to allow the private sector to net save. The argument for a government deficit reduction must be followed by an explanation about its consequences for the private sector balance. Based on trends over the past twenty years we can use as a parameter the external balance average for that period, that is, a current account deficit equal to 2% of GDP, then we can simulate the effects of fiscal austerity on the domestic balance. If the next administration attempts to purse a policy of zero nominal deficits then the domestic balance would run a deficit equal to 2% of GDP, that is, the private sector’s deficit spending. The alternative is for Brazil to turn to current account surpluses, an unlikely scenario to happen. If we are going to bring down the government deficit to zero, then if the private sector is going to save 2% requires a current account surplus equal to 2% of GDP, which requires a very large increase of exports, reduction of imports, and improvement in the factor services balance. This scenario would require a combination of increasing foreign demand, improving terms of trade, and devaluation of the currency to allow for a financial surplus.

Finally, we can simulate a scenario in which we have rising government deficits to offset current account deficits, to allow the domestic private sector balance to generate financial surpluses. In this case, in the presence of current account deficits equal to 4% of GDP, to allow the private sector to net save 2% of GDP, it would require government deficits equal to 6% of GDP. If the private sector is going to save 5% of GDP (equal to the 2002-2007 average pre-crisis) and a current account deficit equal to 4% of GDP then we must have an overall government budget in deficit equal to 9% of GDP. Given the current state of affairs, government deficits of this magnitude might be politically unfeasible right now. Declining primary budget surplus and fears of credit rating downgrade to Brazil’s sovereign debt by S&P and Moody’s already put Ms. Rousseff under growing pressure to cut public spending. Moody’s lowered its outlook to negative and may cut Brazil’s rating to junk. Standard & Poor’s lowered Brazil’s rating at BBB-.

The deficit hysteria pressure came from different sources. From Brazil’s finance minister Mantega, who can be seen as a “deficit dove”, favoring the use of fiscal policy during recessions and advocate surpluses during expansions to repay the debt and pundits like Fraga, who wants spending cuts and can be seen as a “deficit hawk”. In a recent interview, Fraga exposed an orthodox macroeconomic agenda and he claimed, “we haven’t been hitting our budget targets, so we’ve got to get those right to the decimal—no gimmicks.” He went one step further saying, “the government has lost control of inflation”, that is under Rousseff, inflation has soared.

Source: Santander

Feel that price spiral!

The recent rally in Brazil’s stock market has been driven primarily by rising expectations that Dima would not win the election. It is ironic that Brazil’s stocks are soaring as Mr. Neves gains momentum in Brazil’s election as he proposed fiscal austerity to pave the way for economic growth. But, is it already time for early fiscal tightening? The most likely scenario is that Brazil will continue to run current account deficits in the foreseeable future, say equal to the post crisis average equal to 2% of GDP. If policymakers narrow the nominal budget deficit to zero in the next administration then the private sector must run a deficit equal to 2% of GDP (equal to the current account deficit). The private sector deficit (spending more than its income) is dangerous to macroeconomic stability and unsustainable. If the domestic private sector wants to run a surplus (spending less than its income) then the government balance must be above the current account deficit. The policies proposed by opponent Mr. Neves fail to recognize the risks: fiscal austerity poses the danger of recession and even default by indebted households and business. Moreover, contrary to the conventional view, there is no reason to believe that cutting public spending will automatically increase private spending. To be sure, an attempt to impose fiscal austerity at this point, will lead to declines in output, employment, and private spending, thus amplifying the direct effects of government cutbacks and limiting the ability of businesses and households to generate strong cash flows to service their financial obligations. Policymakers must understand that one sector’s financial position cannot be viewed in isolation. They must understand the links between public sector deficits, domestic private sector surpluses, and current account deficits. This is not to say that we should run fiscal deficits forever nor that they cannot be inflationary but following fiscal rules blindly without determining the impacts on the private sector balance can be dangerous to growth and stability.

Much of the concern about public finance in Brazil centers around reducing the public debt burden and debt sustainability. As I have said elsewhere, a sovereign government, which issues its non-convertible currency, is not subject to the same constraints that business, local states, and households face. The Brazilian government issues its own currency, the Real, and has the power to levy and collect taxes denominated on its liability. As in the case of other sovereign countries, it can always service its debt denominated in its currency. However, Brazilian policymakers fear the news of a credit rating downgrade in particular in an election year. They have been operating under the wrong paradigm. Counter to the deficit hysteria view, affordability isn’t an issue as they can always meet their debt obligations denominated in their own currency. Ratings agencies are still clueless on their assessment of default risks of sovereign currency issuing governments. Recent CRAs warnings on Brazil’s credit rating miss the point that Brazil has attained monetary sovereignty. It is the sole issuer of a nonconvertible currency (Reais). It cannot be forced by currency users to default on its domestic debt denominated in local currency.

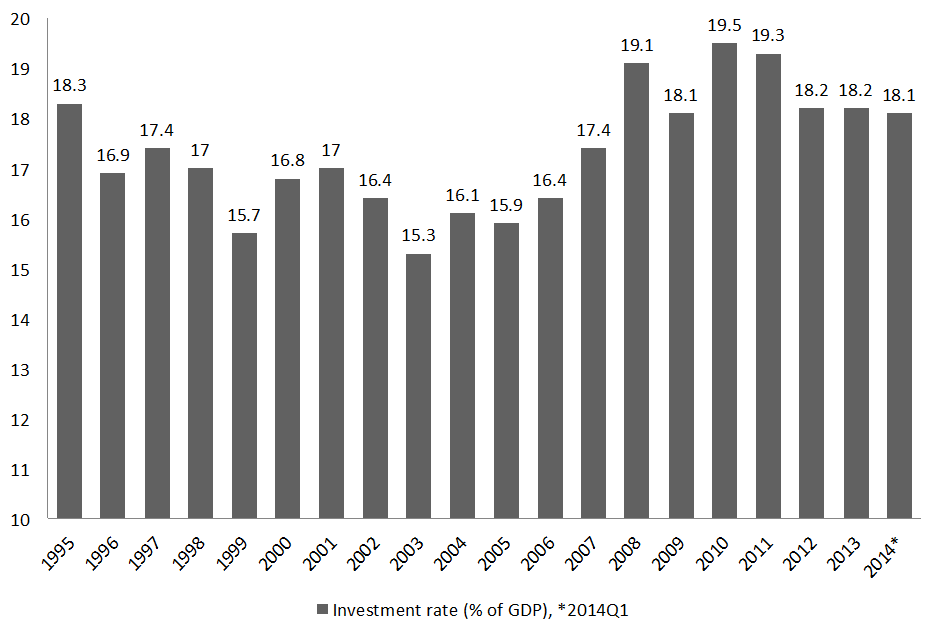

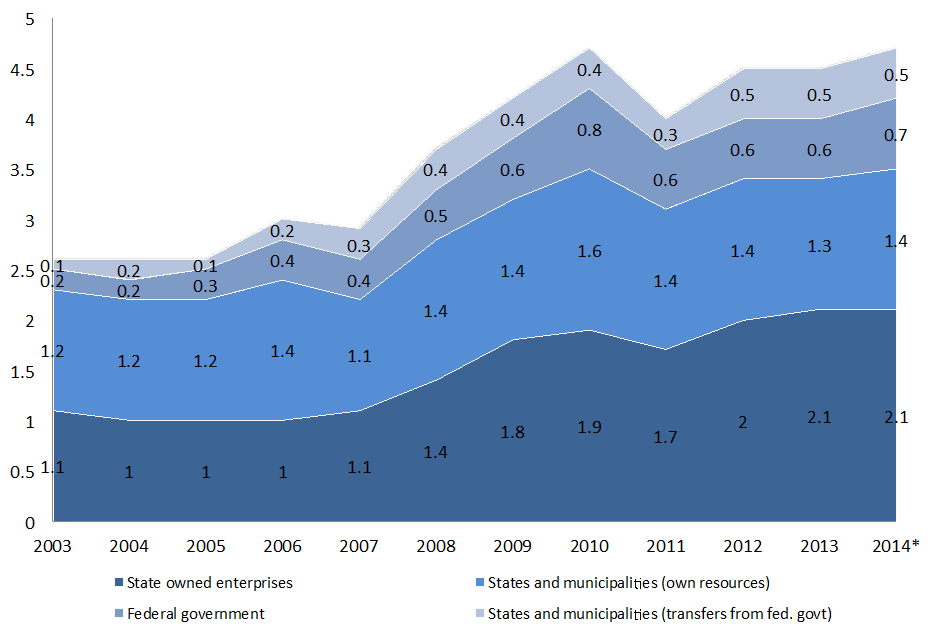

Even though Brazil has a transition policy in place primarily based on public investment, the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC I and II) and a broad program of concessions, it is struggling to shift its development strategy to foster domestic demand growth from one designed to attract external capital and build on external demand.

The Growth Acceleration Program (PAC I and II) notwithstanding, Brazil’s federal public investment public investment is unusually low given Brazil’s infrastructure bottlenecks and investment needs.

Source: MoF

Policy alternatives

How to effectively make the transition to a development strategy based on domestic demand? It is well known that government spending can contribute to productivity lowering private sector costs and through investment in key areas such as infrastructure, health and education, and research and development. Brazil needs to shifts its policy to mobilize domestic resources and adopt an investment-oriented growth strategy. There is ample space for policy to promote infrastructure development in Brazil. For instance, the world economic forum ranks Brazil’s infrastructure 114th out of 148 countries. Even the IMF is calling for an infrastructure push by developing economies. It is crucial to increase government-sponsored infrastructure investment projects as the current rate of federal investment in infrastructure is small compared to Brazil’s investment needs.

Brazil is well known for its high tax burden. It should use the fiscal powers of the federal government to increase government deficit on both fronts, that is, increasing federal government investment in infrastructure and tax cuts for households and firms by simplifying its tax system and providing tax cuts on production, employment, and income. It can close Brazil’s housing gap by 2018 through the expansion of the government program My home, My life. It can implement a national job guarantee program to foster job creation for those willing to work. No worker would get paid less than the minimum wage and those able and willing to work would be employed thus reducing the social costs of unemployment and poverty. Contrary to the conventional belief that a job guarantee program would be inflationary, it can be designed to ensure that the deficit spending is at the right level to ensure and maintain full employment by setting a wage anchor and acts like a buffer stock of the unemployed. The program can be designed not only to provide on the job training but also to increase labor force qualification and the productivity of unemployed workers, which works as an increase in the labor supply. Among its benefits, it reaches social targets by mobilizing resources for additional social services to be provided by the community with gender, racial, and regional effects. This government initiative can be targeted directly to those unemployed workers “at the bottom” of the income distribution leading to improvement of dignity of those that have been denied the opportunity for social inclusion. Moreover, the percentage of the population living in poverty or extreme poverty would be significantly reduced.

Rather than an obsessive concern over budget deficits, the current debate should be over whether Ms. Rousseff’s administration could have gotten more. However, the current administration put itself in a position in which the stimulus measures were too small and short-lived to deal with the challenges posed by the biggest financial meltdown after the Great Depression and this policy initiative is now seen as a failure. As long as policymakers believe that the federal government faces a budget constraint due to the inappropriate application of the household budget constraint to a sovereign government, there will be resistence to adopt an alternative policy. As argued before, they miss the important point that Brazil cannot be forced by markets to default on its domestic debt. It has attained monetary sovereignty, that is, it issues its own non convertible currency.

It remains to be seen whether these policies will be implemented.

[1] Improved external accounts and a surge in capital inflows contributed to the appreciation of the exchange rate and domestic asset prices.

[2] From national accounting identities, dross domestic product (Y) equals the sum of consumption expenditures (C) , investment (I), government purchases (G) and net exports (X – M) that is Y = C + I + G + (X – M). We know that S = I + G – T + CA, rearranging the terms we get: that S – I = G – T + CA where (S – I) the private sector balance equals the government balance plus the current account balance.