Greece: The Impact of Austerity on Migration

by

The chart above documents another striking feature of the impact of the recession on Greece.

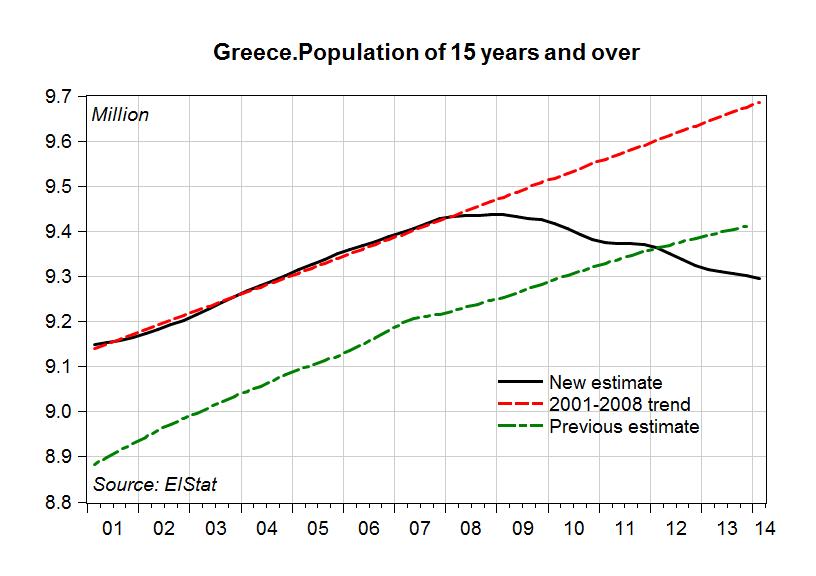

The Hellenic Statistical Authority (ElStat) has recently released the new quarterly data on employment and the labor force, which includes a measure of the population aged 15 or more (Table 1). While the series published in the previous release exhibited a stable upward trend (reported in green in the chart), the new estimates show that population peaked at 9.437 million at the end of 2008, and then started declining, reaching 9.296 million in the first quarter of this year, i.e. it went back to its 2004 level. (The reasons for the change in the series are due to ElStat incorporating the latest census data: details are available in the ElStat web site).

As ElStat does not publish an up-to-date measure of net migration, we assume this could be measured by the distance between the pre-crisis population trend and the actual values. We therefore computed a simple linear trend on the 2001-2008 data, which shows that population would have now been at 9.686 million, had the previous trend continued. The difference between this value and the population reported for the first quarter of 2014 is thus approximately 390,000 people (4 percent).

ElStat makes available the detail by age groups (Table 2), reported in our second chart, which shows that younger Greeks are declining steadily in number – a trend which is common to many developed countries who chose to reduce the average number of kids per family – while the number of older people is steadily increasing – again a trend common to many countries, linked to longer life expectancy. Summing up the 15-29 groups to the 45+ groups, we find that the decline in the younger population accelerated after 2007, compensating the increase in the number of Greeks aged 45 and over, so that the inverted U-shape of the population in our first chart can largely be attributed to the decline in Greek residents aged 30-44, who are now 2.442 million against a peak of 2.544 million at the end of 2008.

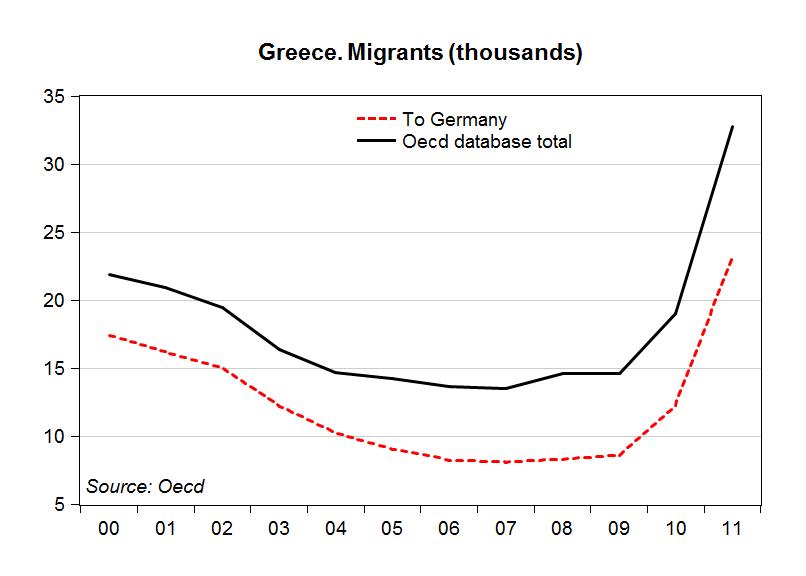

We have no complete information to know if this decrease is due to Greeks in this age cohort migrating abroad, or to a smaller number of immigrants. However, the OECD migration database contains some (incomplete) statistics on immigrants by country (the figures largely under-estimate total migration, as some major European countries such as France and Italy do not report any figures to the OECD).

As the next chart shows, and how it should be expected looking at the respective unemployment rates, the main destination of Greek emigrants is Germany, and the number of migrants has almost doubled from 2010 to 2011 (the last available year).

The other portion of the fall in population is given by migrants to Greece, which have fallen from 65.3 thousands in 2005 to 33.3 thousands in 2010 and 23.2 thousands in 2011.

It is to be expected that migration of Greeks abroad, and the decline in immigrants to Greece, continued on the same paths after 2011, given the size of the unemployment rate in Greece (still at 26.8 percent in March 2014, seasonally adjusted). Using the economists’ jargon, this is another loss of human capital for the Greek economy which will make a recovery more difficult. And, in addition, balance of payments statistics published from the Bank of Greece do not show any improvements in payments made from abroad which could be related to migrants’ remittances: both the compensation of employees received by Greece from abroad, and current transfers to the private sector have actually declined since the beginning of the crisis.