How Profligate Was the Greek Government?

byBreezily blaming the eurozone crisis on government profligacy is a widely-used journalistic shortcut, but by now it should be clear that it’s a shortcut that doesn’t help us understand what went wrong with the euro project. It has been repeated often, though evidently not often enough, that Spain, one of the hardest hit countries, had a public debt-to-GDP ratio that was a mere 27 percent before the crisis hit. And there is reason to believe that even in the case of Greece, the bogeyman of government profligacy, the popular narrative should be treated with a little more skepticism.

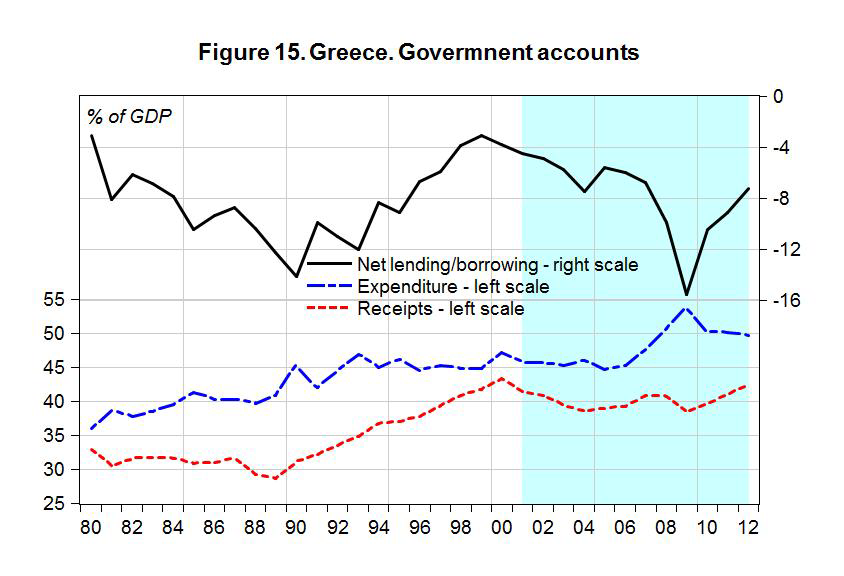

In a new report, Dimitri Papadimitriou, Gennaro Zezza, and Vincent Duwicquet use the “financial balances” approach pioneered by Wynne Godley to look at the recent history and future prospects of growth for the Greek economy. Their analysis of the government accounts includes this graph:

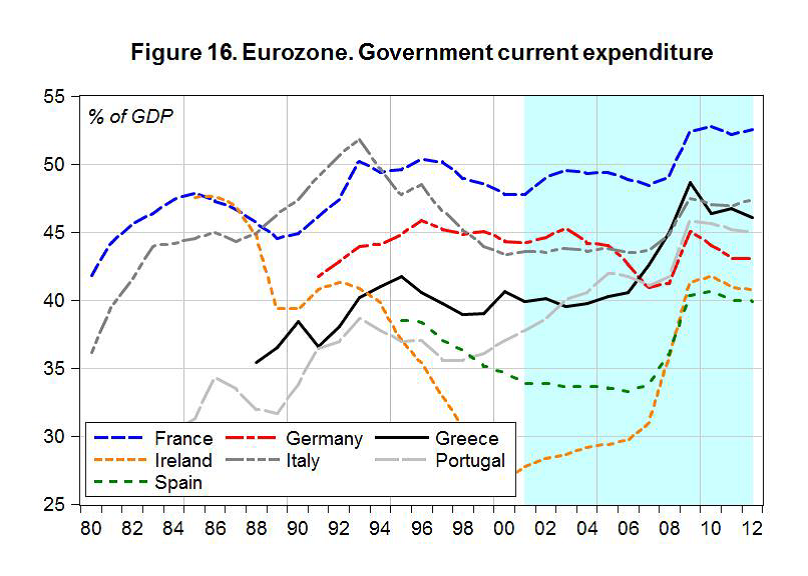

As the authors observe, Greece’s government expenditures were basically stable through the ’90s and most of the 2000s, increasing rapidly only as a result of the 2008 recession (until the austerity programs began to take effect in 2010). Moreover, Greece was not a massive outlier in terms of government spending levels. Prior to the crisis, Greek public spending as a percentage of GDP was on the lower end compared to France, Italy, and Germany:

Papadimitriou, Zezza, and Duwicquet also look at changes in government revenue collection, before and after the adoption of the euro, and they examine the role played by rising interest payments in Greece’s post-crisis increase in government expenditures. But as with most of the other troubled eurozone economies, the major problem for Greece, the authors conclude, can be found in the private sector financial balances:

[G]rowth in Greece during the 2000s—similar to the United States—was fueled by consumption financed by running down households’ financial assets, and/or by net borrowing. It was this unsustainable process, rather than an excessive government deficit, that put Greece on an unsustainable path.

And after mapping out the decrease in net financial assets in Greece (NFA turned negative in 2004), they note that the country is in an even trickier position than some other crisis-wracked nations:

While other countries like Italy still have a net creditor position in the stock of financial assets of the private sector, so that, if necessary, a reduction in government net liabilities can be obtained through appropriation of private financial assets, this possibility is ruled out for Greece, where both the private and the public sector have a net debt against foreigners. As a result, any attempt to quickly reduce the stock of debt must imply a transfer of real, rather than financial, assets from Greece to foreigners.

Download the full report here.