Kick the Can, Please

byAs Dimitri Papadimitriou recently observed, the overwhelming push for austerity in the United States is partly driven by the sense that deficit reduction simply cannot wait:

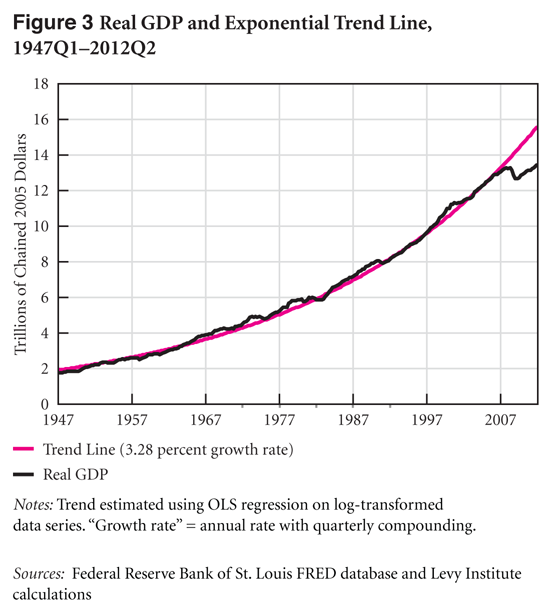

Many in Washington and the media are convinced that the recovery is well underway, and if spending cuts and tax increases are delayed for even a year it will be too late to tame inflation and tighten fiscal policy on a soaring economy. The urgency rests on unfounded optimism. We still have a very long way to go before the economy is anywhere near healthy enough to heat up. The GDP is now, and has long been, far below trend.

Here’s how Papadimitriou and Greg Hannsgen illustrate the point in a recent policy brief:

It is rather odd to be concerned about deficit reduction coming “too late” (i.e. that the black line will rise above the pink line), given how far we are from the historical growth trend. As Papadimitriou and Hannsgen put it: “Based on the present state of the economy, any notion that implementing better policy would be mostly a matter of precise timing is patently absurd. The gap between recent real GDP growth and the historical trend is so large that the danger of overshooting the trend is hard to imagine.”*

Many proposals in this budget battle, including some coming from alleged “deficit doves,” call for replacing the fiscal cliff (over $500 billion in deficit reduction in 2013 alone) with what is essentially a different austerity package spread out over a longer time frame (the consensus target seems to be about $4 trillion of deficit reduction over ten years), otherwise referred to as a “grand bargain” in the media. But notice that even if we continue on our current austerity-lite path (that is to say, without the fiscal cliff and without a grand bargain), and we continue to add jobs at roughly the same rate we’ve been adding them lately, we likely won’t be back to full employment for ten years.

If you are a deficit dove, and you are convinced that the budget deficit will be a problem at some point in the future, but that it should not be addressed until the economy has fully recovered, then your deficit reduction plan shouldn’t even begin for another decade. Obviously, external events could push the current growth path in either direction over the next decade. But the point is that we don’t have any clear sense of when we will be out of our (actual) employment crisis, and it would seem that a deficit dove should want to be reasonably certain that the economy is running at full capacity before pivoting to deficit reduction—particularly since there’s no evidence that the economy is suffering in any measurable way as a result of our current elevated public debt levels. In this context, something David Frum wrote a little while back nicely captures the lunacy of the conventional wisdom: “So the plan is to disregard the crisis we have, to deal with a crisis we don’t have, but might possibly someday have?”

According to Papadimitriou and Hannsgen, the budget sequester should be repealed and not replaced. But if the politics make “repeal and replace” absolutely necessary, they point to proposals such as the one made by Robert Reich, in which deficit reduction would only be triggered when the economy reaches certain levels of employment or growth. If it is not possible to cure Washington of its deficit hysteria, this is the direction in which the policy discussion should move. It will require a fresh debate about the meaning of full employment, and about how much inflation we should tolerate to get there. There have been plenty of conversations about debt and the size of debt, but when it comes to long-term issues, there needs to be more discussion in Washington about what a full employment economy looks like—and whether we’re really committed to reaching it.

* [As Papadimitriou and Hannsgen note, this figure may look different for those who believe that the economy has moved to a “new normal” featuring lower output capacity (that the economy has established a new trend line that lies below the pink line on the right-hand side of the figure). However, the fact that current inflation and inflationary expectations are below the Fed’s already stingy target suggests we probably aren’t close to this supposed lower potential output level either.]