“Stimulus” Isn’t the Best Reason to Support (or Oppose) Infrastructure Spending

by Michael StephensA little while back, Pavlina Tcherneva appeared with Bloomberg’s Joe Weisenthal to talk about the potential infrastructure policy of president-elect Donald Trump. She noted that, contrary to initial assumptions, the upcoming administration may not end up pushing public-debt-financed infrastructure spending, and that if the program simply amounts to tax incentives and public-private partnerships, it won’t be nearly as effective. But Tcherneva added another important dimension to this debate. (You can watch the interview here):

Tcherneva’s point is that infrastructure investment should be determined primarily by the state of dilapidation or obsolescence of our roads, bridges, etc., and not so much by the moment we occupy in the business cycle.

There are some who would argue that the time for a large fiscal stimulus has passed, with unemployment at 4.6 percent and growth continuing apace. There’s a good argument to be made that we’re not at “full employment” even at this moment, and that there’s no need to back off on stimulus (though there’s still the question as to whether the Federal Reserve would attempt to depress economic activity by raising interest rates in response to any substantial fiscal expansion — and, additionally, whether the Fed would succeed in those circumstances). But the point is, where you stand on this debate regarding the business cycle and the meaning of full employment shouldn’t be the driving factor behind infrastructure policy — we shouldn’t necessarily pursue or avoid infrastructure repairs and improvements for those reasons.

Moreover, if you’re looking for a job creation program, which Tcherneva would argue ought to be the point of “stimulus,” there are more effective options. In particular, she advocates a job guarantee that would provide paid employment at a minimally decent wage to all who are willing and able to work. Among other reasons, Tcherneva notes that such a program, which automatically expands during economic downturns and contracts in better times, is more effective as a countercyclical stabilizer, as compared to spending on infrastructure projects (read the tweet-storm version of the argument here).

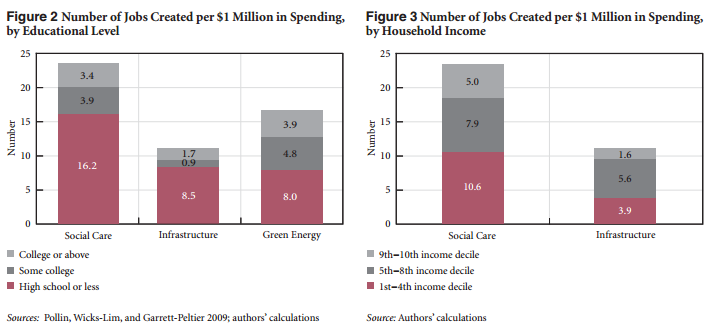

And given that infrastructure seems to have become the go-to spending-side stimulus policy, we might also want to think about the distributive implications. Among the results of this research by Antonopoulos, Kim, Masterson, and Zacharias, which compares infrastructure spending (construction) with a comparable expenditure on direct job creation in the social care sector (early childhood education and home-based care), infrastructure investment not only creates fewer jobs per dollar of expenditure, there is a noticeable gender-based disparity in its employment impact:

With social care investment, over 90 percent of the jobs created are secured by women, whereas approximately 88 percent of infrastructure jobs flow to men. Expanding paid care services largely aids women from low-income households, enhancing household income security by providing a stable paycheck in the event of negative income shocks. (pdf)

And spending on social care more effectively targets those with less education and who are closer to the bottom of the income distribution:

Again, this doesn’t mean we should avoid significant increases in infrastructure spending (the ASCE reports show it’s long overdue). But if our primary goal is to boost inclusive growth and employment, there are better policy tools available. And there are going to be consequences to relying too exclusively on infrastructure spending as an engine of growth.

As for the rather widespread idea that we are at or near “full employment,” Hyman Minsky provides the much-needed alternative perspective (this is from a collection of his work on poverty and policy):

The war against poverty cannot be taken seriously as long as the Administration and the Congress tolerate a 5 percent unemployment rate and frame monetary and fiscal policy with a target of eventually achieving a 4 percent unemployment rate. Only if there are more jobs than available workers over a broad spectrum of occupations and locations can we hope to make a dent on poverty by way of income from employment. To achieve and sustain tight labor markets in the United States requires bolder, more imaginative, and more consistent use of expansionary monetary and fiscal policy to create jobs than we have witnessed to date. […]

The single most important step toward ending poverty in America would be the achieving and sustaining of tight full employment. Tight full employment exists when over a broad cross-section of occupations, industries, and locations, employers, at going wages and salaries, would prefer to employ more workers than they in fact do. Tight full employment is vital for an anti-poverty campaign. It not only will eliminate that poverty which is solely due to unemployment, but, by setting off market processes which tend to raise low wages faster than high wages, it will in time greatly diminish the poverty due to low incomes from jobs.